This article first appeared in the APA Blog on October 7, 2024.

From Sunday July 7 through Thursday July 11 2024, the Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP) held its annual conference at the University of Western Australia in Perth. It’s a lovely spot, looking out at Matilda Bay. It was an international conference, as philosophers from several other nations were represented, including members of the APA. I’ve resided in Perth, off and on, for about 21 years. It was the first time I had heard of anything so enlightened as a philosophy conference coming to these fatal shores. I was excited.

Indeed, I had originally sent in my Abstract when I registered and had it accepted and my presentation penciled in for Wednesday. I’m doing a PhD at the University of New England, which is in New South Wales. My research topic wonders about the future of human consciousness in the Age of AI we have entered. The title of my presentation was “Brain-Computer Interfaces and the Code-Switching of Consciousness.” But I withdrew my Abstract about a week before the event commenced when I learned that the AAP intended to hold an online conference in October, so I switched my Abstract to the later date, glad to have more time to prepare.

So there I was on Day 1, standing outside the Duxton Hotel, across the street from the American consulate, waiting for my Uber ride to arrive. The organizers of the conference had set up the schedule of events on an app called Whova. I so looked forward to seeing and hearing Iain McGilchrist. But alas he would not be keynoting until Thursday morning. Scottish psychiatrist. Lots of buzz. But today, I would sit in on less celebrated lights. The keynote was to be delivered by Dean Rickles, on the subject “Jootsing,” which apparently referred to a kind of nuanced jumping-into Reality. I didn’t feel up to it.

Instead, I decided to go to an afternoon presentation delivered by Michael Newall, “Iconic Mental Representation and Panpsychism.” Newall is Australian. He’d been all around though. He’d taught in the UK. He’d won two of the American Society for Aesthetics’s major awards. But I was drawn to his more recent work in the philosophy of perception, as I was a big Merleau-Ponty fan. Newall had written a recent article, “Painting with Impossible Colors,” which “argues for impossible colors by inducing their experience in observers.” I could see how this form of ‘jootsing’ might have a bearing on arguments over emergence in the study of panpsychism.

I arrived early, registered at a table, and plucked my ID badge and clamped it onto the drawstring of my hoodie. Then I threaded my way through the milling philosophers nibbling on finger foods and sipping on urn coffee. They were quiet and respectful. I hadn’t felt that sense of being amongst Goodness for so long, maybe since my days of Sunday Mass, everyone trying to be good -- at least during the elapsing of the rites and rituals and sermon. I made my way to the cafe and ordered a latte, paying for it with my phone, but fumbling with the app, the young cashier losing patience, even though I was the only one in line. I felt old and irrelevant to her. She belonged to a generation that ‘canceled’ in a heartbeat. Nice coffee though. I sat and just absorbed the buzz of philosophers at work, respectful, thinking aloud to each other, reading, sussing, and gently jootsing each other’s reality.

I took my latte to Newall’s session. He had his slides up on the wall and was going on about “all consciousness is representation.” I wondered about that. Could it be true? He explained that his thesis involved an iconization of the representational in such a way that -- drat, he turned and I didn’t catch what he said. He talked of “causal interdependence” (CI). There’s lots of that in theses and in talks these days -- inter and intra. It’s not new; it’s retro; but, frankly, it’s still refreshing. Me, I’m an interpenetrability-of-all-things kind of guy. How could you call yourself a panpsychist and not swing that way?

Newall argues for a “master map of locations in the brain.” He considers ever so briefly “the combination problem.” He cites Treisman, I nod. He returns to CI and recommends these thoughts:

CI plays a large part in explaining the patterns and extent of consciousness as we experience it, partly because the CI on which perceptual content depends is insulated from the multitude of other states of CI that are a feature of the world. That suggests a panpsychist conclusion.

Exactly as I had it. Oh, brave new world that has such minds in it. Then it was over, like at a planetarium, lights coming on, illusion lifted, back to the dark concourse you came from. Sagan and Vangelis -- poof! -- back to the cafe for another latte.

Next, I made my way to UWA professor Miri Albahari’s “Is there a worm in the panpsychist apple? Help me find out”. I arrived late. No seats. My condition would not allow me to stand long, but I leaned against the wall, left, then right. Boy. was she lively, bouncing around. She wore clothing that exposed her scrawny hairy legs (can I say that?), but what energy! A worm in an apple can’t be very good. I thought of Eve, then I thought of The Conqueror Worm. Of course, that’s Poe. Miri’s proposition went a bit like this:

I argued that with a foot still planted in the materialist camp, panpsychists had not actually closed the mind-matter gap as so often proclaimed. The gap had simply migrated to the definition of matter. To overcome the inner-outer gap problem, as I call it, panpsychists must renounce observer-independent structures and have everything unfold from within consciousness.

It was to be interactive, Miri inviting the audience to help her locate the worm in the apple and give it a right drumming. Well, as I say, it was standing room only -- for me. But I couldn’t hang around for the full exposition of her energetic and provocative en garde. I felt ill. Woozy. I crept out, hoping nobody suspected me of being a worm on the lam.

I ordered up an Uber and in just a few minutes an Aussie driver showed up with his electric car, a Tesla. Nice. Nice ride. Quiet. He dropped me off at the Duxton.

Day 2

I was ill. I pulled up my Whova app on the pocket computer (aka cellphone) and tried to motivate myself to overcome my fog (no, I hadn’t had a drop of alcohol the night before) by parsing through the offerings at the Philosophy. “The Buddhist Theory of No Self.” Christ, I could relate to that right about now, I thought. But no oomph grabbed me by the impetus. At 11 AM there was a panel discussion I had every intention of attending: “Climate Ethics and Intergenerational Justice: Indigenous, Institutionalist, and Social Practice Perspectives.” It was to feature a panel discussion with local Aboriginal elders. It promised to deliver wise words from the world’s oldest human cultures on sharing the abundant resources of the only place in the universe known to have life and light. Plenty of impetus, but no Can Do. I slept some more. I slept all day and well into the middle of the night. When I learned through Whova that someone at the Philosophy had tested positive for Covid-19, I wondered if I had been sprayed.

Day 3

Anik Waldow, a German researcher at the University of Sydney, was keynote with “Self-Enactment in the Face of Doubt: A Deep Dive into Montaigne’s Essays.” I love Montaigne, so I was definitely ready to dive right in. How do you overcome the doubt? she asked. Her answer is ‘intermingling’, friendship. Find someone you can trust. Nice sentiments, but perhaps naive? Keynote?

I took a deep breath, decided to get another latte, priming up my cell phone payment app ahead of time so as not to frustrate (again) the cashier with my ineptitude.

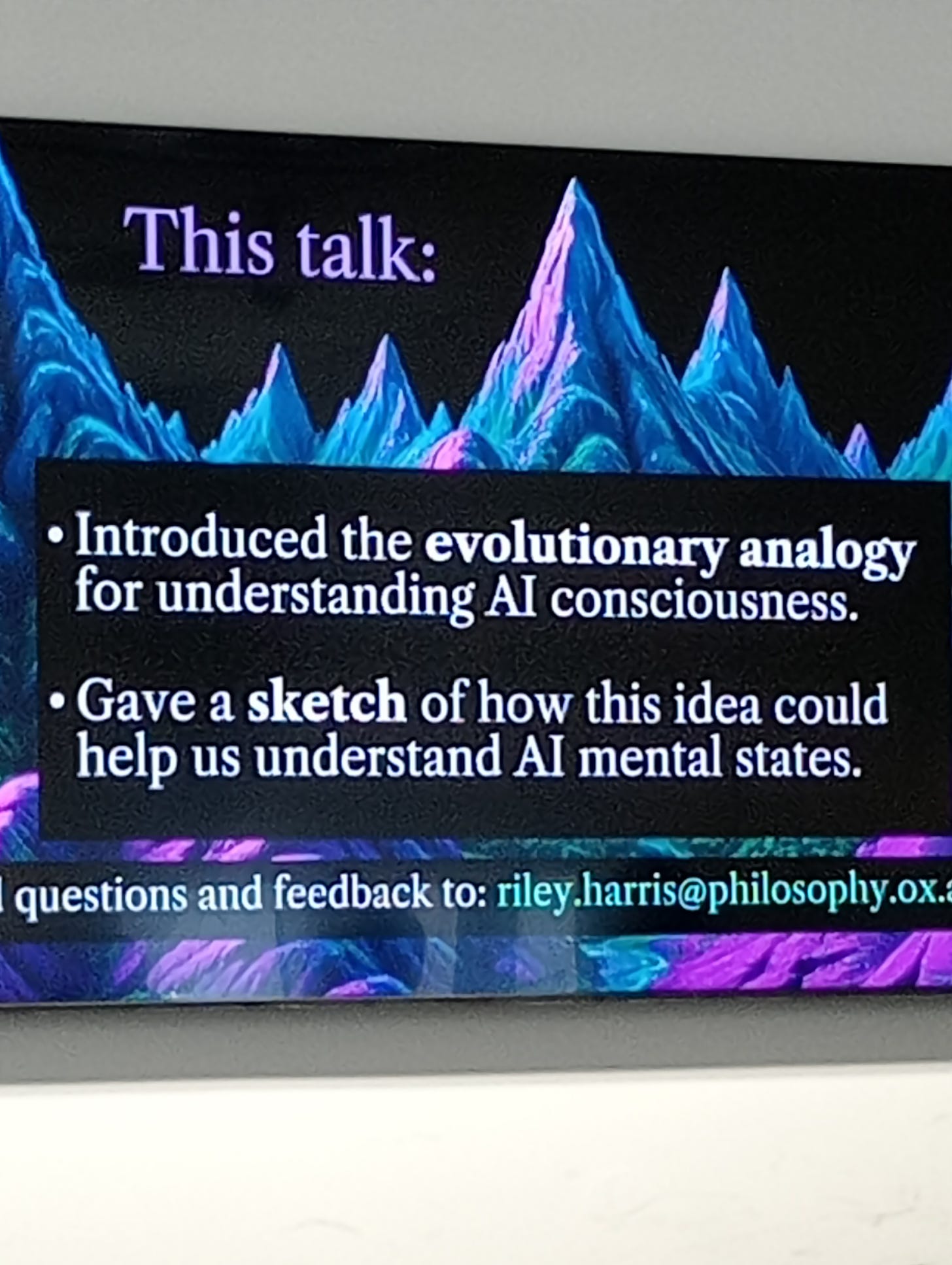

At “Can Evolution Help Us Understand AI Mental States?” Riley Harris, a PhD student at Oxford, argued that, yes, it can. I was keened. This was to be my bailiwick. Harris explained,

About half of philosophers believe that we might build conscious AI systems in the future. If this becomes reality, it seems that training will play a crucial role in shaping the minds of AI systems, much like evolution shapes the minds of organisms.

Of course, it really depends on what we mean by conscious. Conscious like humans or conscious like machines? Which is better? What if evolution decides the machines are better?

I needed to sleep. I wanted to attend the Aboriginal session this evening and would need the energy, so I called an Uber and a nice Indian driver dropped me off at the hotel and I lifted to my room and immediately crashed on the bed and slept. I overslept and missed the “Koora-ang Kadidjiny – Quoppadar Boorda – Learning from the Past – For a Better Tomorrow.” Hopeless.

Day 4

The Big Day.

Iain McGilchrist was keynote speaker. He had recently put out the two-volume set, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World. I was ready. He came with much hype. I was ready to receive the wisdom of McGilchrist.

McGilchrist is a psychiatrist by profession and that was the first thing he wanted to make clear as he began. I was expecting him to be broguish, like Scotty from Star Trek, all fiery and permanently irked. But McGilchrist is a mild man, well-spoken, brogue tamed by an excellent education. His topic was “Bergson and the Brain: What Can Neuroscience Learn from Philosophy?” Meaty enough.

I wasn’t especially familiar with Bergson’s work, but McGilchrist treated us to a suave explanation of brain lateralization and the roles the left and right lobes play in consciousness and other mind activities. McGilchrist said,

Henri Bergson, anticipated the findings of recent research into brain lateralisation, by associating the differences between two ways of understanding the world discoverable on introspection with differences in attention. In doing so he, and others such as William James, unknowingly predicted the phenomenological differences associated with the workings of the two cerebral hemispheres.

Phenomenology got my heightened attention. It was Merleau-Ponty who had provided me with the first shivers of what would become my junkie’s frisson re: interpenetrability of all things and minds.

McGilchrist’s project here is to rejoin the schism he believes has developed between neuroscience and philosophy. I’m moved to know that McGilchrist, a scientist, does not want philosophy to be regarded as an epiphenomenal activity. His differentiation of Left and Right lobes is a fairly convincing demonstration of the need each lobe has for the other. If the left and right were locked in a Hegelian master-slave struggle, McGilchrist wants the right lobe to have the upper hand. It’s the lobe that drives our ‘attention’. He says:

I think it is of considerable importance in any quest for truth. The nature of the attention we exhibit towards the world governs what we find there. Attention changes the experiential world -- the only world we can know. It gives us not only what we see, but the nature of what we see. Hence, attention is a moral act. It changes the world and it changes us. This cannot be ignored if our goal is to have something to say about reality.

Attention is a moral act. How about that? Sounds like McGilchrist is one woke fellow, as today’s kids would say.

McGilchrist was humorous at times. Many of us quite enjoyed his taking the mickey out of Descartes, essentially referring to his Cogito as the proposition of a schizophrenic. A snark, which, coming from a psychiatrist, was shockingly jowl-jolly. This is madness.

I got an Uber back to the Duxton. In the morning I showered and went downstairs to have my last buffet breakfast. Across the street from the American consulate that looks up at the Chevron building. I waited for my partner to come and drive me home to the hills of Perth. It was my first philosophy conference, and I felt better prepared to present my own work in the conference to come in October.